A patient's guide to cataract surgery and lens implants

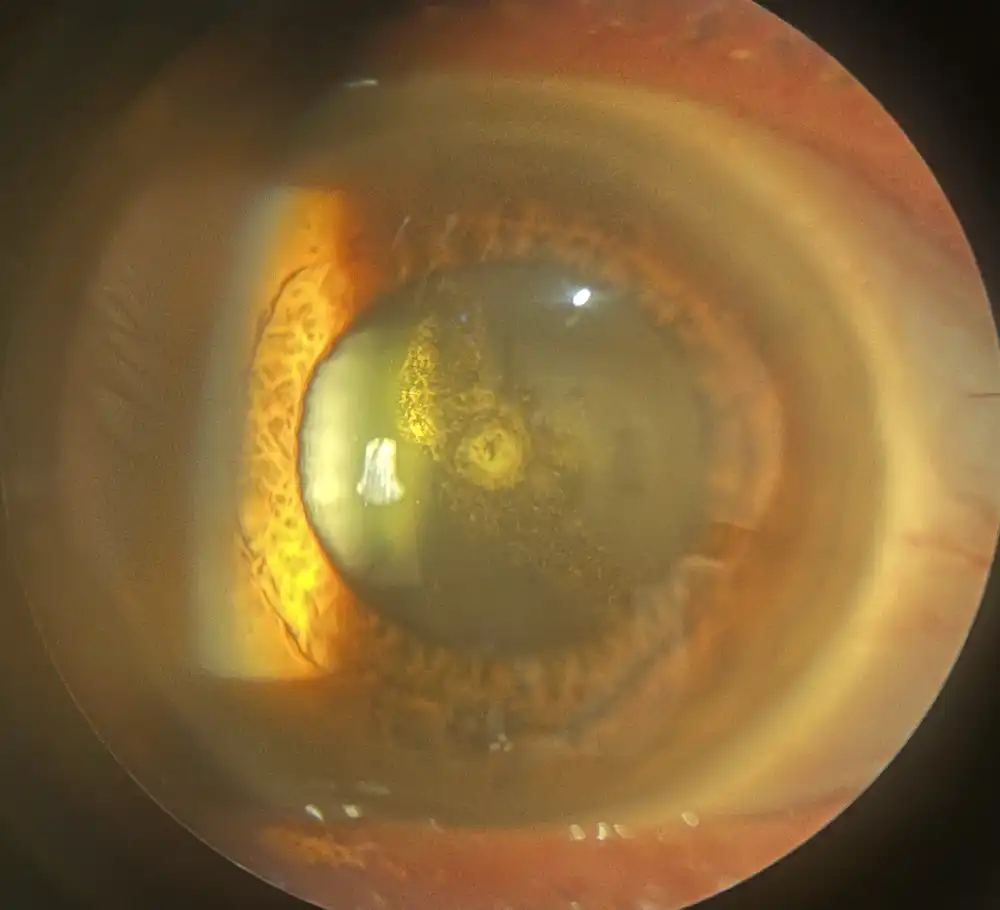

The inside of your eye contains a lens that focuses light. As you age, the lens gradually becomes less clear. When the lens becomes yellowed or cloudy, we call it a cataract. A mild cataract won’t affect your vision much, but it may change the prescription in your glasses. Cataracts gradually worsen, and eventually your vision will be blurry in a way that glasses can’t correct. Difficulty reading and bothersome glare—particularly when driving at night—are common complaints.

How do I know when it’s time for cataract surgery?

Only a doctor can tell you if cataracts are the cause of your vision problem. Once you’re certain that cataracts are the reason you aren’t seeing well, the decision to operate is based on several factors:

- How bad are your symptoms? If you are struggling with your usual tasks (reading, driving), your surgeon is much more likely to recommend cataract extraction. Symptoms are usually the primary reason for proceeding with surgery.

- How much has your vision declined? In most cases, your ability to read a vision chart will be reduced by a cataract. Some patients have very severe symptoms, despite being able to read a vision chart well, but if your vision is measurably reduced the doctor is more likely to recommend surgery. A particularly important threshold is the vision requirement for maintaining your driver licence. If you fall below this threshold and you still want to drive, surgery may be recommended.

- How fast is your prescription changing? If your glasses prescription is changing very rapidly, you might want earlier surgery. In addition, glasses can only improve some of the symptoms of cataract. The overall quality of your vision may be poor, even with updated glasses. During an evaluation for cataract surgery, a lot of emphasis is placed on how much your symptoms can be improved with glasses alone.

- How strong is the prescription in your glasses? Surgeons often try to correct your prescription at the time of cataract surgery (more on how they do that below). If you have a very strong prescription, operating on just one eye can lead to a big difference in prescription between your eyes. This can cause a sensation of eye strain or imbalance. As a result, surgeons are more likely to wait until you are ready for surgery in both eyes. Doing the surgeries closer together (typically 2–4 weeks apart) will minimise the amount of time that you have to cope with a large difference between your eyes. If you have a very mild prescription, operating on one eye is usually not a problem.

Ultimately, cataract surgery is an elective procedure, and we typically operate when you reach a point where you are unhappy with your vision. Other lifestyle factors—such as your age, occupation, or hobbies—are also taken into consideration.

What happens during cataract surgery?

In most cases, cataract surgery is an outpatient procedure, requiring a few hours in a hospital or day surgery. The surgery requires you to lay still for about 30 minutes, but you won’t need to hold your eye open. If you have difficulty lying completely flat due to breathing problems or joint pain, it’s important to discuss this with your surgeon ahead of time.

Your experience will consist of several stages:

- Dilating the eye: In order to access the cataract, your pupil needs to be widely dilated. This is usually done by giving several rounds of eye drops over a 15 to 30-minute period.

- Local anesthesia: Most cataract surgery can be performed without a general anesthetic, which means that you don’t need a breathing tube, and you are usually awake during the surgery. If needed, your anesthetist can give intravenous medications to help with anxiety. The surface of your eye is numbed using anesthetic drops. The eye can be further numbed by injecting medication inside the eye (during the surgery), or by injecting anesthetic to block the nerves that supply your eye (before the surgery). The amount of movement or light that you see during the surgery depends on the details of your anesthesia, but in all cases the goal is for you to be comfortable and pain-free.

- Preparing the eye: The eye and surrounding skin are washed with antiseptic solution, and a drape is applied to keep the field sterile. The drape covers your face, but you will have an oxygen mask and plenty of room to breathe.

- Removing the cataract: Small incisions are made in the cornea, the clear tissue just in front of your pupil. The capsule holding the lens is opened, and ultrasound is used to break the lens up and remove it. The machine makes different sounds to give feedback to the surgeon, and it is normal for you to hear these noises.

- Inserting the implant: The empty lens capsule is expanded with a surgical gel, and a plastic lens implant is injected to replace the lens that was removed. The implant is positioned, the gel is removed from the eye, and the incisions are sealed. It’s common to inject antibiotic and steroid preparations at the end of the surgery.

- Dressing the eye: The drape is removed and a protective shield or sterile dressing is applied. After a short recovery, you will be able to go home.

When will I notice improvement in my vision?

Some people have good vision within a day of surgery, and others require time to reach their best vision. If you are in the group that needs a bit more time, you shouldn’t worry. Here are some reasons your recovery might not be immediate:

- A dense cataract: Surgeons attempt to minimise the amount of ultrasound energy used to break up the cataract, but there are practical limits to how much the ultrasound can be reduced. If your cataract is very advanced, it may require more energy to remove it. This energy causes swelling that blurs your vision, and you will not have your best vision until the swelling subsides.

- Adapting to your lens implant: Some implants use technology that requires your brain to adapt before you experience the full benefit of the lens (the different types of lens implants are described in detail below). If you are having surgery in both eyes, it is often easier to adjust to the implant after both eyes have been operated.

- Updating your glasses: It isn’t always possible to achieve independence from glasses with cataract surgery. If you have a very strong prescription, high levels of astigmatism (oval-shaped eye), or variable preoperative measurements, it may be necessary to correct your vision with glasses. In most cases where glasses are required, the strength of your prescription will be lower than it was before surgery. If you are in this group, it’s best to wait 4–6 weeks for your prescription to settle before obtaining new glasses.

What type of lens implant should I choose?

The most important decision you will make before your cataract surgery is to choose your surgeon. Once you’ve found a surgeon you trust, they can make specific recommendations to help you select an implant lens. All modern lens implants are of high quality, and will usually last for the rest of your life. The implants come in three broad categories, and each has different tradeoffs:

- Monofocal implants are the most common type. They provide high-quality vision, but they don’t completely eliminate the need for glasses. A common approach is to aim for clear distance vision (driving, television), and then use reading glasses for near work. Monofocal implants are popular because patients adapt to them easily, and the results of surgery are fairly predictable.

- Enhanced depth of field implants are similar to monofocal implants, but they provide a larger range of clear vision. We sometimes refer to this improvement as better intermediate vision (in the middle distance, just beyond arm’s reach). Computer work is a common example of a task that requires good intermediate vision. These implants have fewer optical tradeoffs than multifocal implants (below), but don’t completely eliminate the need for glasses when reading or working up close.

- Multifocal implants give the widest range of vision, and in some cases can completely eliminate the need for glasses. Many patients with this type of implant report that they see soft halos around lights in dim lighting (night driving). These optical artifacts are usually not bothersome, and occur because of the technology that allows the lens to provide both near and far vision. You should choose a multifocal implant if eliminating the need for glasses is your top priority, and you don’t mind taking some time to adapt to the implant. Multifocal implants are not suitable for everyone. If you have high levels of astigmatism (oval eye shape), retinal or optic nerve conditions (macular degeneration, glaucoma), or problems with eye alignment (double vision), you may have trouble adjusting to a multifocal lens.

There are many strategies for using these three types of implants to achieve specific goals. Talk to your surgeon about the tasks that are highest priority for you.

What determines my need for glasses after surgery?

Before you have cataract surgery, the doctor will measure your eye with a machine called a biometer. The biometer provides information about the length and shape of your eye, which is then entered into a formula that calculates the correct lens implant for you. Even though the goal is to completely correct your prescription with the implant lens, there are a number of reasons why that might not be possible:

- Measurement quality: The machine takes multiple sets of measurements. If they match exactly, there is a greater chance that they are accurate. Sometimes the measurements are very variable (dry eyes, very dense cataract, movement during the test), making it harder to be certain of the correct lens power.

- Mathematical variation: Different mathematical formulas can give different results for the same patient. It’s common for the doctor to run several formulas and compare them, but these formulas make certain assumptions about your eye, and can only estimate the correct lens implant for you.

- Intentional undercorrection: If either the measurements or the formula results are highly variable, the doctor will need to leave some room for error. When choosing the implant, they will usually err on the side of being slightly nearsighted, as patients tend to prefer nearsightedness (myopia) to farsightedness (hyperopia).

- Implant availability: Lens implants are available in certain powers, but the perfect implant for you won’t exactly match the available powers. The doctor will need to pick the implant that most closely matches your measurements.

- Variable healing: The formulas used to calculate your implant lens are based on an estimation of where the lens will be positioned after you are done healing. If your eye heals with the lens in a slightly different position, it can change your prescription.

- Implant limitations: As previously mentioned, the most common implants can only correct your vision at one distance (near, far). That means you will require glasses some of the time, even if your outcome is perfect.

Keep in mind that your surgeon is trained to consider all of these factors. They will choose an implant with a high likelihood of matching your prescription, and add a safety margin that is appropriate for your measurements. If you have specific goals, such as a particular activity you would like to do without glasses, it’s important to communicate that to your surgeon.

If you have further questions about cataract surgery and your options, feel free to contact us at Vic Eye for a consultation.